Take a deep dive into the early Midwestern Hardcore scene and explore its impact within a larger framework of Rave culture.

Known as America’s Heartland, the Midwest not only offers beautiful landscapes and generally kind people but also plays a vital role in the nation’s farming and manufacturing sectors. With its low cost of living and low-stress lifestyles, it usually isn’t considered an area where cultural production takes place, especially when compared to the coasts on either side. That’s not to say the Midwest is culturally destitute or lacks cultural capital, but rather has a sense of cultural reticence or modesty that encourages not challenging the status quo. This could be why it comes as a surprise to many that the Midwest, more specifically Wisconsin and Minnesota, offered one of the most vibrant rave scenes of the ’90s.

The Midwest is responsible for a lot of electronic music, with Techno hailing from Detroit and House serving as the theme music for Chicago’s Clubland. However, the unlicensed fraction of the Midwestern scene allowed its participants to take part in a cultural production that was both free from strictures and innovative. Along Interstate 94, particularly around the Twin Cities (Minneapolis and St. Paul), Milwaukee, and Madison, a vast number of unlicensed raves took place, featuring a diverse assortment of genres and styles. Made up of ravers, DJs, promoters, record labels, and fan zines, the subculture offered a space that was both defined and designed by its members. Today, we will focus on one of the pioneering forces of this avant-garde – the Midwestern Hardcorps.

Favouring higher BPMs, harder kicks, and lots of distortion, The Hardcorps refers to the Hardcore Techno fraction of the rave scene. While Techno and House music had already become international exports, Milwaukee had a large output of Hardcore, and producers in Minneapolis were developing their own form of Hardcore, Hard Acid. Pioneered by DJ ESP aka Woody Mcbride, Hard Acid would be a harsh and uniquely Midwestern sound characterized by distorted Roland TB-303 bass lines. As a result, The Hardcorps organized some of the meanest soundtracked raves the States ever saw, and is the reason some people refer to this scene as one of the most underrated ever.

[bandcamp width=100% height=120 album=1757816930 size=large bgcol=ffffff linkcol=0687f5 tracklist=false artwork=small]

WOODY MCBRIDE

My own introduction to the Hardcorps’ sound started with DJ/Producer and promoter Woody McBride. Originally hailing from Bismarck, North Dakota, Mcbride moved to Minneapolis to study in ’88. At first, he experienced a huge culture shock but soon found his place in the early House scene. He started DJing and working in a record store while being mentored by Kevin Cole and Thomas Spiegel, two DJs who promoted the first House music parties in Minneapolis.

Spiegel, considered the Godfather of the scene, was the first promoter to bring the ‘wall of sound’ concept to the Midwest; stacking speakers on top of each other to create a literal wall of sound is still an essential trope of the scene to this day. Speigel’s Thursday night residency at the 7th St. Entry, “House Nation Under a Groove,” served as a hub for local talent as well as a place for international acts to share new music.

Mcbride would eventually put on the first Techno shows in warehouses across the Twin Cities. In the beginning, he would tell building owners he was ‘shooting a video’ inside their space, and nobody was clued into what was really going on. His actions would solidify a strong scene with a dedicated crowd. Mcbride was also responsible for an event where 3,500 people turned up from all over the country to welcome back Richie Hawtin after his two-year ban from the States.

His development of the Hard Acid sound was majorly influenced by Freddy Fresh, who taught Mcbride about analogue gear and synths, including where to source them and how to produce with them. Freddy’s knowledge, mixed with Mcbride’s energy and belief in the power of dance music, was crucial in the evolution of the scene and what would come next in the Midwest. Mcbride launched his own Communique Records in 1994 and went on to release music on many significant labels, including Fatboy Slim’s Skint, Josh Wink’s Ovum, and Dave Clarke’s Noise.

Eventually, Mcbride’s music and promotional expertise brought him East towards the Drop Bass Network in Wisconsin, although he continued to promote events in the Twin Cities with his “Bassgasm” series. For anyone interested in what’s currently going on in the Twin Cities, Kajunga Records is a good starting point; their podcast series on SoundCloud features tons of local talent.

DROP BASS NETWORK

At the head of Hardcorps, the Drop Bass Network (DBN) and its founders Kurt Eckes and Patrick Spencer were hosting raves as early as 1992. Since its inception 30 years ago, the Milwaukee-based label and rave promotion unit has been a stronghold for Midwestern Rave music. They not only hosted some of the biggest raves in the Midwest during the ’90s, but were also responsible for the legendary Furthur parties.

Furthur was a series of Techno campouts hosted by Kurt Eckes alongside Woody Mcbride with his Communique label and Journalist/Rave Promoter David Prince. These Campouts would ultimately capture and encapsulate the power, creativity, and aesthetic of this scene perfectly, but more about that in a moment.

The idea for the campout came to Eckes when reading The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, a book about the “Merry Pranksters” who travelled the states as psychedelic missionaries, turning people on to LSD and its transcendental qualities. The Futhur concept took a similar undertaking, turning people on to Acid Techno and the power rave has to bring like-minded people together. The Pranksters had embarked on their mission in a van that had the word “Further” misspelled across the front; Eckes chose this name as a nod to the pranksters as he embarked on his own psychedelic crusade.

Let us take a moment to picture one of the most significant of the Furthur parties, Even Furthur ’96. It’s Memorial Day weekend, and around 3,000 excited ravers litter a rural Wisconsin field surrounded by cars, camper vans, and trailers with license plates from as far as Florida and Arizona making up the space in every direction. Sundown is approaching, and there’s a buzz of energy infecting everyone as groups huddle around campfires, grilling food and preparing for the night’s antics. There is no official lighting, and there’s certainly no security.

The crowd is all rocking classic ’90s gear. Dark and neutral tones make up most of the colour spectrum aside from the occasional kandi raver prototype rocking bright colours and synthetic fabrics. Everyone is wearing the baggiest “Judge None Choose One” jeans or camouflage trousers, most of which are covered in mud from the knees down due to the previous night’s downpour of rain. In fact, most of the festival grounds have turned into a muddy swamp. The main two tents that make up the festival have flooded, creating a treacherously slippy dance floor.

Soon you’ll be heading towards those tents, where around 100 musicians will be performing a wide range of dance music. Over the next three days, you’ll hear plenty of Gabber and Hard Acid Techno, as well as a large amount of Jungle. San Francisco trailblazer Scott Hardkiss will premier his remix of Elton John’s “Rocket Man,” Mix Master Morris will spin a six-hour Ambient Jungle set to protest the large amount of Gabber, and Daft Punk will make their American debut.

It may not seem like it, but what you are picturing is the Midwestern rave scene at its finest. This is Furthur, a valuable piece of dance music history that would underpin all subsequent movements in the US Rave scene.

Ultimately the fabled Furthur was the first of its kind in the US, having started in ’94 and running till 2001 before taking a temporary hiatus. The festival returned in 2016 and has been running annually since. Aside from the headliners of ’96, some highlights from the Furthur series also include Aphex Twin, Perc, Ansome, and Minneapolis’ own DVS1, who regularly spins at the infamous Berghain club in Berlin.

Despite many successful years, it is clear that Even Furthur 1996 was emblematic of the strength that the Midwestern Hardcorps had in store. The festival broke new ground in the US, while greatly resembling the free festivals or teknivals that had started in the UK, and by ’96 were taking place all around Europe, namely France, Italy, and the Czech Republic.

The concept developed through traveler culture and was ultimately shaped by the Spiral Tribe, an influence that we will see reoccurring throughout this story. DBN would even license and publish a CD compilation entitled Sound Of Teknival featuring tracks from SP23, aka Spiral Tribe, but there is a lot of controversy surrounding that disk. The Paris-based record shop and distribution company Techno Import had originally plagiarized the CD from SP23 prior to its US release with DBN.

The Teknival serves as ground zero for musical experimentation and new ideas which evade capitalist strictures of corporate deals and entry fees, while no-door policies create a meeting point for people from all walks of life. The DIY approach is one of the defining features of this culture; unlike clubs or commercial festivals, events are often free from corporate sponsors, overbearing and oppressive security and dress codes.

Like Furthur, many different mobile sound systems come together to make up the teknival, and the infrastructure usually lacks any of the stage construction common to a commercial festival. Freedom is the name game when it comes to these types of gatherings, and as Eckes said himself at Even Furthur “There are no rules here at all.” Furthur gained iconic status after ’96 and became a reference point for all that would follow in the Midwestern scene, but how did this come to fruition?

THE BEGINNING

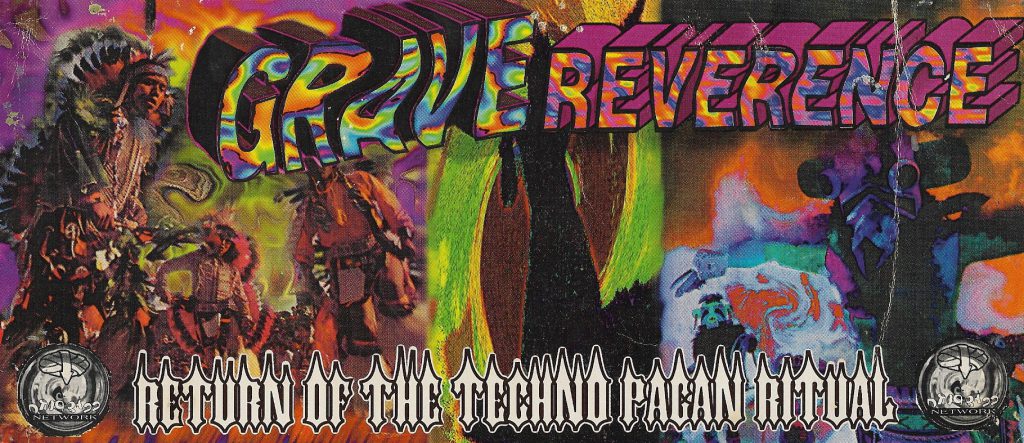

The story really starts in 1992, Kurt Eckes and his roommate Patrick Spencer begin throwing parties under the Drop Bass Network moniker. Around September of that year, DBN was still defining its style until Eckes reads about a Spiral Tribe party in the UK being described as a Techno Pagan Ritual, and an idea began to manifest. DBN takes on a dark and somewhat occult image with satanic references and gothic fonts defining the label stylistically. Along with this, a distinctly uncompromising attitude surrounds DBN, an attitude that often comes with the territory of throwing DIY parties.

In line with representing the darker side of rave music, DBN opts for Hard Acid and Gabber music and would quickly become a pioneering label in the sound. Eckes had discovered these harder sounds while visiting Staten Island with Tommie Sunshine. In those days, New York had its own booming Hardcore Rave and club scene, but that’s a story for another time. The pair went to a Storm rave, and Tommie had initially told Eckes not to transpose the new sound back to the midwest, fearing that drug use would escalate alongside the harder music.

The aesthetic and attitude of the Techno Pagan vibe are what make Eckes an anomaly in the scene. At the time, the PLUR ideology was very present within both the beliefs and stylistic codes of rave culture. But Techno Paganism seemed Anti-PLUR, and as Tommie suggested, the harder music invited harder drugs. Inevitably DBN parties did become an endurance test for even the most seasoned ravers.

It has been speculated that the dark aesthetic that DBN branded itself with was a marketing ploy meant to attract Midwestern Heavy-metal kids. The Midwest had a large Metal scene, and the use of satanic and dark imagery may have turned some of those kids on to hard electronic music. This idea may have stemmed from Eckes’ infatuation with Kiss as a youth. This marketing strategy is perhaps most apparent with DBN’s sub-label SixSixtySix, which was reserved for the hardest, fastest, and most punishing tracks to come out of the Midwest.

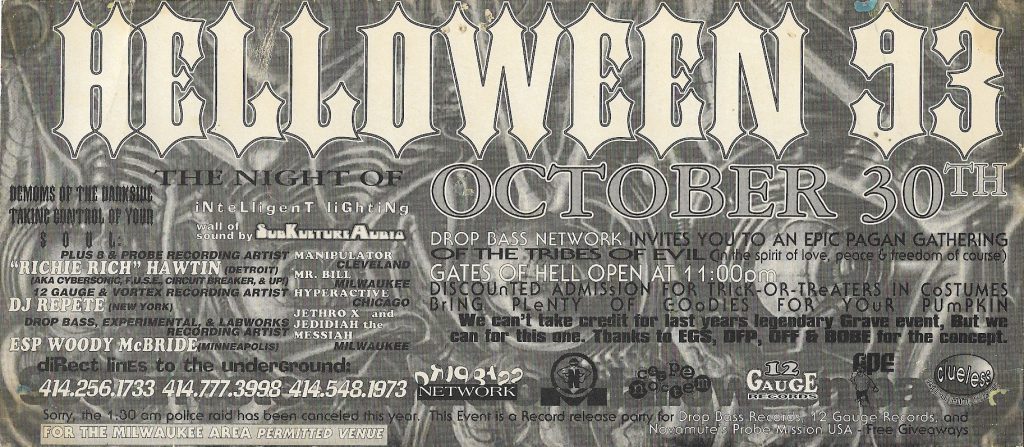

Much like many other incarnations of dance music, the Midwestern scene would experience police antagonism. One example of the police exercising unnecessary force was on Halloween night in 1992, an event called Grave would be subject to the harassment of law enforcement. Close to a thousand people were arrested and issued citations of $325 after police stormed the warehouse located just north of the Menomonee River, close to what is now the Great Lakes Distillery.

The organizers and participants were issued fines close to an overall sum of $300,000. Although it’s unclear how much of a hand Eckes and Spencer played in promoting the party, this event played a large hand in both publicizing and aiding the growth of the scene, as well as creating DBN’s future audience. As part of their heavy-handed response, The Milwaukee Police Department issued the fines for “aiding and abetting the unlicensed serving of alcohol” when in fact, just a few beers were found.

In the midst of bad publicity for a clear overreaction, it was also stated by police that a pound and a half of cannabis and a few nitrous oxide canisters were also seized. Although according to witness testimonies, a large number of ecstasy pills that were being sold at the bar went completely undetected. The charges would eventually be dropped, and most of the fines would go unpaid; this is mostly due to one of the arrested’s father, a lawyer who took on City Hall and won. In an act of utter defiance, DBN would host Grave Reverence the following year on Halloween, with the tagline “Return Of The Techno Pagan Ritual – Demons Of The Darkside Taking Control Of Your Soul.”

Grave also bared a resemblance to the UK raves that were happening at the time. Following suit with the UK precedent, participants needed to have access to a phone number or “info line” where the details of the party were announced. To evade police detection, tickets would be picked up in one location and maps in another, a plan which evidently failed.

A LINK TO THE SPIRALS – POLICE OPPOSITION

The aggressive measures taken by police at Grave mirror the numerous times similar tactics would be employed by law enforcement against unlicensed events. It’s a tendency that can be seen throughout the history of dance music and dates back as far as the jazz clubs of Prohibition-era America and the Swingjugend of 1930s Germany. Much like the contemporary rave, these scenes became enveloped in a struggle for their own existence.

The police hostility is perhaps the most obvious link between the Hardcorps and the Spirals, meaning that the police exercising their power against the Hardcorps could indicate that they were doing it right. After all, the Spirals are considered to have done it right, and they certainly experienced heavy policing.

The best illustration of this comes from the same year as Grave. The Spiral Tribe held a rave on Easter Sunday in a warehouse on Acton Lane in West London. The Metropolitan Police’s Territorial Support Group (TSG) surrounded the structure in the early morning, sparking a 10-hour standoff. Witnesses state that the TSG were masked and had their ID numbers covered. Once inside the warehouse, they began beating and arresting everyone.

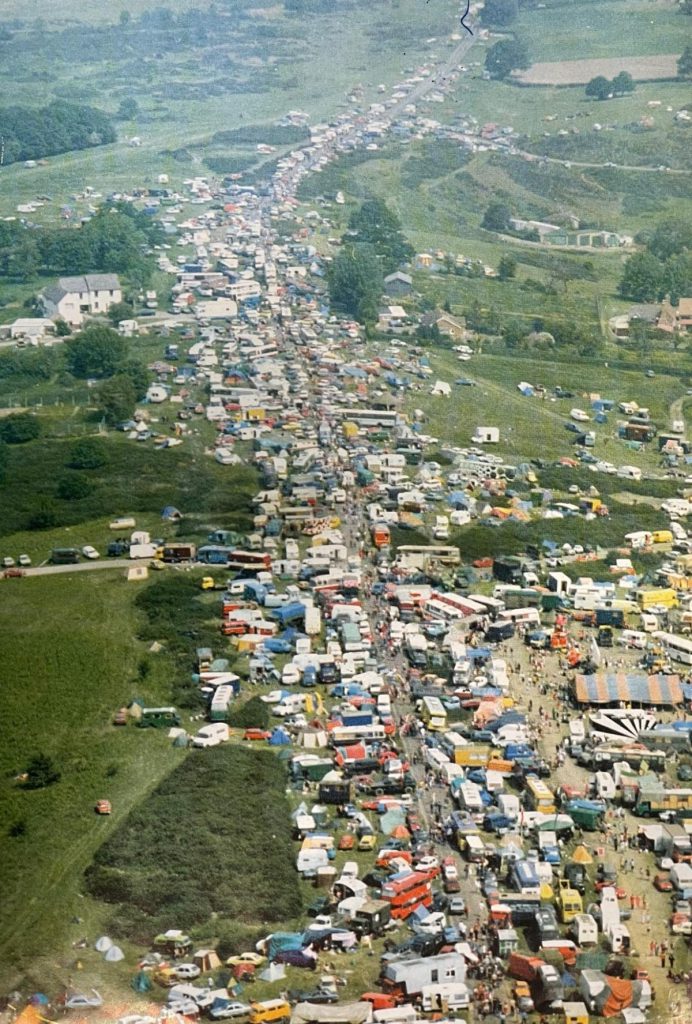

Following the TSG assault, the Spirals and ten other sound systems would host the infamous Castle Morton Common Teknival. The size of the free celebration was unprecedented; an estimated 30,000 individuals attended. UK media outlets had a field day, mostly portraying the incident negatively. Similar to how Furthur embodied the growing rave movement and its impact, Castle Morton did the same.

Sharing, openness, and inclusion were the cornerstones of the rave movement, values that should be acceptable in society but wouldn’t be tolerated by governments with the ideologies of privatization. Legislative measures against unlicensed parties were implemented in the UK as a consequence of pressure from concerned citizens and alcohol industry lobbyists who believed the new phenomenon was having a negative impact on the number of young people drinking.

The Criminal Justice Act of 1994 gave the police power to stop parties, which, defined by section 63(1)(b), incorporated “sounds wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.” This piece of legislation, aimed at raves, was the first time that a government had used such aggressive tactics to end an entire culture. The States would see a similar response to rave in 2003 with the implementation of the Reducing American’s Vulnerability to Ecstasy Act (RAVE act), written by former senator and now President Joe Biden.

TAZ: FURTHUR AS AN EMBODIMENT OF THE TEMPORARY AUTONOMOUS ZONE

Efforts to contain, control, and regulate the scene, efforts that turned raves into commercial spaces, have to do with what an unlicensed event can represent. Illegal raves embraced a DIY ethic similar to punk culture, repurposing technologies in order to avoid the corporate music industry and studios while creating one’s own channels of production and distribution. Autonomy from major labels allowed for the development of a much faster and darker soundscape, giving birth to Hard Techno and its sub-genres like Acid Techno.

Along with this, the autonomy from corporate sponsorship deals, and lack of restrictive entry policies, mixed with open-minded philosophies, culminate in what anarchist writer Hakim Bey called the Temporary Autonomous Zone (TAZ); meaning a space that evades formal structures of control, built by a system of non-hierarchical social relationships. It’s clear how the definition of a TAZ applies to the Furthur Festival series and the illegal raves that took place in the Midwest.

The formal aim of the TAZ is to create a space that can assist the liberation of participants’ minds from the systems of control that have been imposed on them. This direct refusal of societal norms and resistance to control, as well as government “suspicions” of drug trafficking, is considered one reason why raves are policed so heavily. The congregation of so many non-conformists, in a space free from strictures, can be seen as a breeding ground for new and radical ideas, thus posing a threat to organized government. Although this idea may seem ridiculous to many involved in rave culture, it’s evident in the fact that from 1990 until now, there are many examples of police brutality and legislative measures being taken against the scene worldwide.

FINAL THOUGHTS

If there’s one thing I can ascertain from my research into the history of dance music and cultural theory, it’s that every “new thing” has a lineage from somewhere, and there will always be a chain of subsequent movements and styles that follow. It would be easy to claim that what the Hardcorps represents is part of a much larger legacy that was kicked off by the Spirals and the traveler movement. A simple link within a linear timeline, however, I think Midwestern Hardcore music stands for something more.

Adding to this, a common narrative is often told about the history of dance music. This narrative states that after the birth of House and Techno, the music was never as appreciated in the United States as it would be in Europe. In 1989 the UK’s youth was reacting and revolting to ten years of oppression under Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative rule and the Implementation of Neoliberalism. A similar reaction to Reagan informed the US rave scene. Meanwhile, in Germany, or more specifically Berlin, the youth were reacting to the dissolving of the Eastern Block and the fall of the wall; Kids from the East and West were able to congregate for the first time in abandoned spaces to an entirely new soundtrack.

Dance music and the rave phenomena thus served as a cure for the hardship. Of course, this idea of dance music serving the oppressed or marginalized is true to all major developments within EDM culture, and it is undeniable that what happened in 1989 marks Dance Music’s largest introduction into mainstream culture. The US-made music would spawn a large number of European producers who would supposedly take control of the sound and are responsible for the inception of all later genres.

For example, Rotterdam Records (RR) is a label often cited as being the innovator of Gabber alongside Planet Core Productions (PCP), who brought Hardcore Techno into the underground tradition. The first project that RR ever worked on was the mixing for Low Spirit Recordings Mayday Compilation Vol. II, which featured the track “Less Is More” by X-Crash. X-Crash was the duo name of Adam X and Jimmy Crash, both of which were pioneers of the New York Techno scene alongside Adam’s brother Frankie Bones (all of whom featured on DBN and played at Furthur). Interestingly, only two years later, the same track would be released on Drop Bass Network.

Meanwhile, Lenny Dee’s New York-based label Industrial Strength was releasing Hardcore as of 1991, the first release being a reissue of a PCP record and one of the first hardcore tracks ever, Marc Acardipane’s “We Have Arrived.” What I am illustrating here is a synergy between European and American producers, which is often ignored.

[bandcamp width=100% height=120 album=1047722272 size=large bgcol=ffffff linkcol=0687f5 tracklist=false artwork=small track=770061604]v

What happened with Acid Techno is similar. Artists like Plastikman (Richie Hawtin), Hardfloor, and Dave Clarke are often cited as having inspired the genre, while the London Acid Techno scene of the mid-90s is considered the starting point of the genre. Artists like D.A.V.E. The Drummer, DDR, The Geezer and The Liberators and their Stay Up Forever Collective (SUF), with its multitude of sub-labels, are thought of as the driving force of the sound.

It’s the 1997 compilation It’s Not Intelligent…And It’s Not From Detroit…But It’s F**king ‘Avin It that was the determinant factor that solidified the tropes of the genre as well as putting the London Squat party scene at the heart of the sound. However, a quick listen to the back catalogue of DBN will indicate that the Acid Techno sound had already been developed to a sophisticated degree as early as 1993.

By this logic, it is safe to say that Hardcorps stands out as an anomaly and not just another step in a linear narrative. Although the influence from the Spirals is as clear as it is in any other unlicensed rave scene, the Midwest’s need to produce its own culture, not just being consumers but rather shaping something, is what makes this scene just as valuable as any other major contribution to the culture.

Much like the queer spaces that allowed for House to develop, and the need for a reimagining of the senses that Techno was born from, it’s clear that the scene we have discussed was born from a necessity of its participants. It is for this reason that the raw energy and creativeness of the Midwestern Hardcorps should be considered both a serious and beautiful contribution to electronic dance music.

Follow Drop Bass Network on Social Media:

Website | Facebook | Instagram | SoundCloud | YouTube

Follow Woody Mcbride on Social Media:

Website | Facebook | SoundCloud | YouTube

The author mentioned a party w 3500 people to welcome Richie Hawtin.bacj to the US. The name of that party was Stairway to Headphones, March 1997. I was at that and Furthur 96. This article is a great encapsulation of the scene I came up in and inspired me to keep involved nearly 30 years later.