Focused on the industry-shaking 2010 EDC in Los Angeles and containing nearly twenty years of footage, The Last Dance is an exhaustively researched documentary.

The Last Dance is nothing if not ambitious. Narrated by director Le Liu, the documentary weaves a personal story of his own growing involvement with harm reduction into the larger tapestry of the infamous 2010 EDC at the L.A. Coliseum and its fallout. It tackles a huge range of topics, from DanceSafe’s influence on public policy and bunk MDMA studies to media witch-hunts and government crackdowns. Scores of interviews give insight on every level, from the festival attendee all the way up to the government bureaucrat.

Yet, despite the absurd amount of research, the documentary struggles to find a compelling argument. It can’t quite decide what exactly EDC 2010 changed, besides everything. Check it out below and read on for my take on what this documentary did well and where it missed the mark.

Watch The Last Dance on Vimeo:

https://vimeo.com/313317814

First, let’s talk about the good.

There are several chunks that are must-sees for anyone interested in the history of either the rave scene or harm reduction, spanning the first 40 or so minutes of the documentary. While it skimps on providing the context behind the scenes, the extensive footage from over two decades of raving in the US is frequently fascinating.

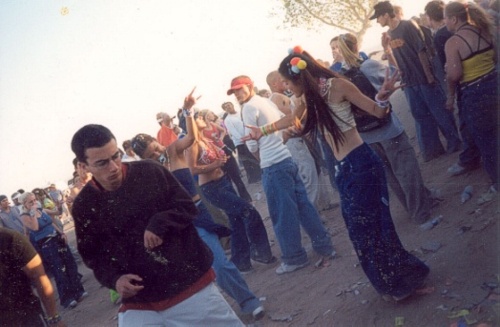

Early footage of the first few EDCs, held in the Shrine Auditorium and other venues across California, charts the early days of the festival, where crowds as small as 5,000 were considered normal. Other videos from long-forgotten festivals like Together As One (Insomniac’s collaborative NYE event) and shut-down venues like Home Base. Pictures of ravers from all decades create an unmistakable connection, carrying the eerie feeling that they could have been taken yesterday.

The US harm reduction scene is given similar care. Liu’s deep connection to the organization DanceSafe is one of the centerpieces of the documentary’s narrative, as he joins the group right as harm reduction breaks into the mainstream. Founded on the principle that providing drug education that wasn’t being taught in schools was the best way to keep people safe, DanceSafe quickly found itself thrust onto the national stage when these controversial ideas were picked up by the local media crew. Their rise, which takes some unexpected, positive turns, is one of the strongest narratives in the movie.

One of the documentary’s greatest strengths (and biggest weakness) is the breadth of topics discussed.

Within the first 40 minutes, Liu covers the underground rave scene, disaster response at EDC Las Vegas 2012, what it means to be a raver, D.A.R.E., DanceSafe, a history of ecstasy use in America, media demonization of rave culture, killer pills, the R.A.V.E. act, and the myth that MDMA punches holes in your brain. And this is all before properly discussing the main event, EDC Los Angeles 2010.

That grab-bag of topics is great for someone like me who already has a familiarity with each of them, but is probably more than a little confusing for those that don’t. Liu never dives too deep into each topic, and pings around between them without drawing solid connections. While all of them are a part of the puzzle explaining how EDC LA 2010 fell apart, Liu gives the viewer no hints on how they might all eventually fit together. Many of the details are presented without dates, too, which makes the whole timeline extremely confusing.

Once we finally reach EDC Los Angeles 2010, the documentary begins to slow down and take its time with its subject, but still refuses to draw conclusions.

Anchored by an interview with a 2010 attendee, the middle section of the film goes about explaining just what happened at and around the last EDC at the L.A. Coliseum. However, the interview, like all interviews in the film about the event, isn’t concerned with trying to tie to a higher thesis or conclusion about the event and simple play out as a record of experience. Ok, so everyone who went thought it was awesome; what does that tell us?

I feel like Liu really wants to hammer home that the media blew EDC LA out of proportion, but looking from the outside in it is hard to look past the flagrant violations to health and safety that plagued the event. Even worse, the few sources they interview fail to explain why that EDC was so unforgettable, so irreplaceable. Compared to future editions of EDC, it looked like hell: crammed shoulder to shoulder with little room to breathe, rushing barricades just to get to friends, dying of thirst, reeking of shit and piss as everyone did their business wherever they could. Judging from the pictures, the whole event was a deathtrap.

The second half of the film is broken up into two overlong segments: the media fallout from EDC LA 2010, and the harm reduction response.

After the death of a fifteen-year-old girl at EDC LA 2010, calls to ban raves were commonplace amongst the media and the government at large. Liu covers largely the raver’s response to these accusations, never really digging any deeper than ‘they were blown out of proportion.’ It would have been nice to draw explicit connections to the topics introduced earlier, such as early ecstasy deaths and media moralizing, to help understand why the media latched on to it the way it did.

As such, I found it difficult to buy entirely into the ‘witch hunt’ angle. Insomniac has made so many smart moves in the years since 2010 that make each edition of Electric Daisy Carnival more safe, accessible, and just plain fun. It feels weird that the documentary spends so much time defending an EDC where someone died because proper safety features weren’t implemented.

One of the stronger parts of this segment, however, is about getting to the bottom of what happened to the girl who passed away.

While the media branded it as an MDMA overdose, the actual content of MDMA in her blood was far below the overdose limit. Instead, the real cause was hyponatremia, a classic cause of death for women in MDMA-related instances. Hyponatremia occurs when someone consumes too much water, too fast, usually caused by the body heating up from taking MDMA.

Here is where Liu makes his point perfectly. If there had been harm reduction services at the event, or harm reduction education available in the world at large, then perhaps the girl would have internalized DanceSafe‘s famous saying: ‘Drink water, but not too much water’. Here, drug education could have directly prevented a death (Liu doesn’t get into what else would have helped: efficient emergency services, such as Ground Control and EMTs, which could have reached the girl quickly and minimized the damage).

The documentary then moves to the aftermath and the government’s progressive response that almost feels too good to be true.

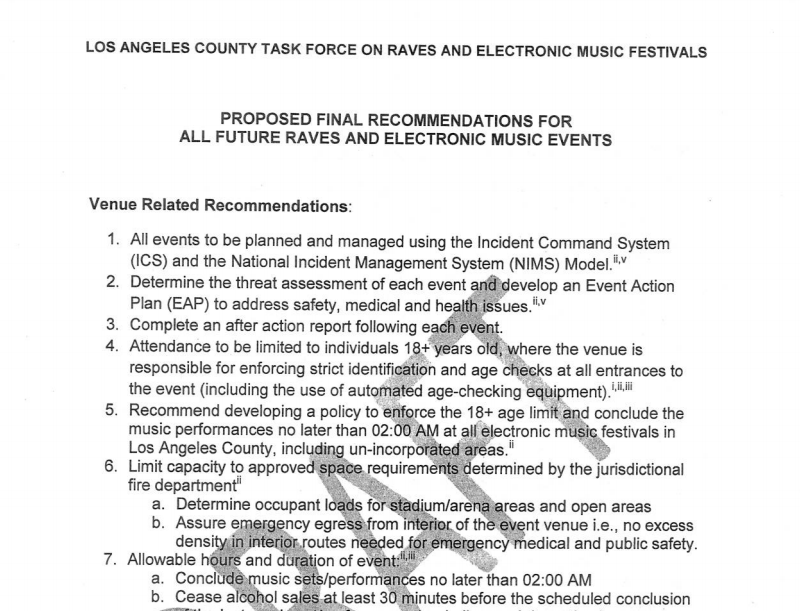

Instead of banning raves altogether, the L.A. City Council decided to work directly with members in the harm reduction community to create a task force to implement educational services throughout raves in the city. This included handing out government-sponsored, non-judgemental flyers on the facts about various drugs and a list of health and safety principles that all future. However, EDC eventually gets kicked out of the city, and the initiative dropped. But for a brief, fleeting moment, our government actually seemed to be taking the correct approach.

This section, beyond lasting for about twenty minutes too long, misses an important point that I would have loved to see highlighted.

While the L.A. task force died in 2010, the list of principles went on to become the foundation of events hosted by Insomniac in the future. Things like the over-18 age limit and free water stations have become standard at Insomniac shows. It represents a one-to-one connection to the policies that Insomniac now implement at all of their festivals, but Liu never ties them together. He just lets it hang in the air, and then moves on to a different topic.

This relates to the documentary’s biggest problem: its lack of a satisfying conclusion.

As the documentary speeds to its end, it fails to tie together all the parallel threads that have been running through it since the beginning. It never explicitly states what EDC 2010 changed: was it the public’s perception of raves? The codifying of harm reduction principles into mainstream event production? Is it the changing nature of raves in the post-coliseum, post-Big-Room-boom era? The documentary asks all these questions but never explicitly connects them with the evidence previously presented. I know they exist, because I’ve seen them happen in the scene myself, but anyone who’s a casual rave fan might feel lost. It makes an aimless movie even more scattered.

Here’s an example. In the very beginning, Liu talks about attending EDC Las Vegas 2012, his first in the Las Vegas Motor Speedway. He arrives there late, and after a few hours, they begin to shut down the venue due to aggressive winds. Initially worried, he’s impressed by Insomniac’s response, an efficient and organized evacuation that manages to get everybody out of the danger zone safely.

The obvious connection here is the difference in preparation between the 2010 and 2012 EDCs.

In 2010, chaos reigned. People barreled past security guards and parkoured their way across the coliseum. Lil Jon pleaded fence jumpers to stop in the name of love and light, and they just kept jumping. There was just one entrance into mainstage — one!! — and it took three hours to get all the way through it.

But in 2012, after two years of intense media scrutiny and governmental pressure, Insomniac had their shit together. Everything went smoothly; there were no people jumping fences, trampling other attendees, or stuck somewhere where they couldn’t access water.

That’s the story there, an obvious connection of how the disastrous response of the 2010 EDC led to an incredible response just two years later.

EDC went from a wolf-pit, an every-person-for-themselves disaster waiting to happen to an event so well-organized that they could safely evacuate 100,000 in a few hours time. What a story that would be, tracing what went wrong at 2010 and how it motivated Insomniac to drastically change for the better.

But Liu doesn’t go there. He pivots to a completely different topic, talking to 2012 attendees about the negative media perception surrounding the 2010 event and…it’s gone. Forgotten. Superseded by another idea that seems disconnected from what we just saw and heard. It’s frustrating.

That’s how I felt throughout the whole documentary: frustrated.

There is so much good stuff here, so many great interviews with great people about doing great things. There’s so much footage that transports you to a different time and place that still feels like it could have been yesterday. On top of that, the amount of debunking and myth-busting paired with concrete data that you can show to people and say, ‘here, what I love to do isn’t as scary or dangerous as it’s been portrayed’ is massive.

But all that good is tangled in a string of ideas that never come together. They never connect. They weave in and out of each other, popping up for one moment before disappearing for an hour, never properly building to a satisfying argument. By the end, when Liu closes with a statement from Insomniac wistfully vowing to return to the Coliseum one day, I threw up my hands in frustration. The old rave culture is dead, Liu seems to say, it died with EDCLA 2010. But I feel he failed to properly tell us why…