The early rave scene wasn’t all sunshine and lollipops. Let’s explore the myths and realities of the past, how the scene evolved, and the lessons we’ve learned.

There’s a ton of nostalgia for the ’90s rave scene these days. Some of it comes from those of us who were there, but way more comes from a younger generation of ravers. Not the ones entering the scene today; that cohort is simply caught up in excitement as they discover their happy place. It comes from the group just before them, the ones that have been in the scene for maybe three to ten years.

Regardless, I’m here to tell you that some of this nostalgia is entirely misplaced, and even more is misunderstood. I promise this won’t be about the good, ole days! In fact, I’m here to tell you it wasn’t all as good as it appears in the rearview mirror.

Don’t get me wrong, the ’90s had some awesome qualities! But the question remains: Was the scene inherently better at that time? There’s no way to answer that because everything is subjective, and our memory of the past is so often biased. So with that, let’s explore what the rave scene really was in the ’90s, how it’s evolved into what we have today, and lessons from the past that we may (or may not) want to apply to our future.

One important question, “Just what is a rave, anyway?”

Ah, this is a great question! Ask 100 ravers, and I’ll bet you’ll get nearly 100 different answers. There may be overlap, but no two ravers will see this the same exact way. This is a blessing and a curse, but I think way more of a blessing. This ambiguity allows each of us to make the scene what we desire. It also speaks to the origins of a time when every event was truly created by and for the community. Event organizers have famously said that they didn’t create any of this; they just gave the community a place to show off its art. And wild personalities!

Even doing an internet search for the definition of a rave isn’t helpful. JDNB explains that the term in the ’50s with “wild bohemian parties of the Soho beatnik set.” It later became more closely associated with electronic music in the ’80s, which is still mostly true today. But there are so many components to events that really feel like raves that it defies definition. There are many elements that can make up a rave, including high-energy music, dancing with abandon, drug (and alcohol) use, and sleep deprivation. Taking it further, you’ll likely find raves in dark spaces, with light shows and wild costumes. Finally, raves are often defined by their sense of community amongst a diverse crowd and also as a place to escape.

These are just a few examples and I’ll bet you are already thinking of examples where some or many of these are missing. You may also notice the inclusion of “community” and “escape,” which can arguably have opposing meanings. The concept of PLUR doesn’t date back to rave origins, but it is connected to the 90s and a direct result of the focus on community over individuals. Today, there’s an often heated discussion about how individuals trying to escape are ruining the community. Can’t both of these exist together?

The early rave scene was ripe with DIY and truly underground, often illegal, events.

The ’90s were a transition decade as the rave scene went from relative obscurity into the mainstream. Yet throughout the decade, raves met the criteria listed above, more or less. However, two key differences set them apart from what we (usually) experience today.

First, most were truly DIY. There weren’t sound system rental stores, and there certainly wasn’t anything like Amazon from which to shop for materials to create art. Instead, the community gathered what was needed to throw an event. Music, lights, art, and even a bar were all optional based on what the community could scrape together. Yes, over time, organizers bought gear. But just as many raves were free and the community created the art and the scene. Still others had no merch or bar; instead resourceful partiers brought their own and sold to each other. Or simply traded with each other.

Second, nearly all raves were illegal (and this was arguably in the definition at the time!). Organizers found an abandoned warehouse, or an empty field, and just set out to make a party happen. And by doing this at a time when authorities didn’t even know to stop them, these events became autonomous zones.

Autonomous zones are most often associated with protest camps and intentional communities. Both apply here.

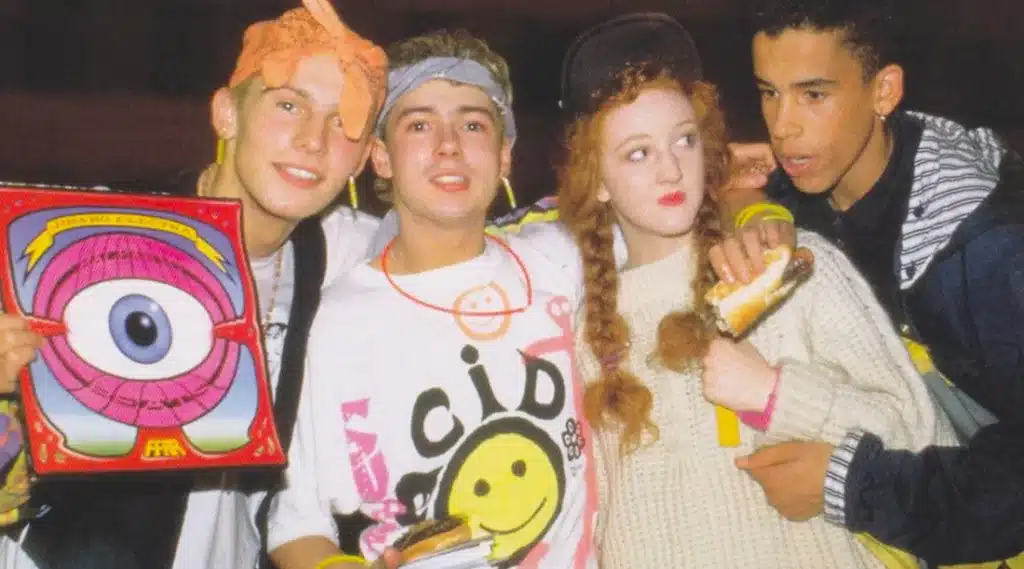

Early ravers were quite often young, oppressed, and angry at the world around them. They were also often from marginalized communities that didn’t have a megaphone to speak through. So when they banded together, they found a strength that didn’t exist in their everyday life. Better still, this strength wasn’t coming from a single marginalized community. It came from putting so many different communities together just to party and enjoy themselves together.

By the very nature of being illegal, these events were acts of protest. And when these otherwise disconnected people connected at a rave, they created an intentional community. They also had the power to control their space – be it for the night, the weekend, or even a week. They knew they’d return to what Burners call “The Default World,” but they also knew they’d return stronger.

Authorities didn’t know what to do with early raves. They often approached active raves and were effectively turned away by the crowd, either through false assurances that there was “nothing to see here” or through the vicious energy of the ravers themselves. Either way, police often determined it was better to let the party run its course than to interfere, resulting in more and more events taking advantage of this model.

DIY and illegal parties could only go so far, and they’d eventually fade into the mainstream. Mostly.

Illegal events eventually attract too much attention. This results in authorities shutting them down or events melting into the mainstream. While both happened here, it’s arguable that the mainstream was the bigger culprit. However, many organizers who lived through the transition will also tell you that, after getting shut down enough, they realized they could throw legal parties with less risk and make them feel underground. This became the future of the rave.

That isn’t to say that DIY is dead, and every event is legal. It just means that more of the events now are highly curated and produced in legal, often very polished, spaces. The DIY scene still exists, and some lament that it’s hard to find these events. To those I simply remind them that finding a Friday night rave in the ’90s was often a game of scavenger hunt and phone tag wrapped in a geo-location model well before cell phones or personal GPS devices. So, yeah, they were always hard to find… And that is what makes each of them so special!

The bottom line is that 2024 isn’t better, or worse, than 1994 – it’s just different.

Raves have stood the test of time because they have evolved. There are many desirable elements that have been lost over time, but also some pretty incredible things that have been gained as well. It would be great if raves were all autonomous zones again, but very few locations can truly pull that off. And it would be great if the scene was more community-focused. At the same time, we now have incredible displays of art and anonymous crowds where individuals can really escape from reality, if only for a few hours.

If you are truly nostalgic and want to live, or relive, the early days through stories, I strongly recommend the Rave To The Grave podcast episodes with Flapjack (Part 1 / Part 2) and Jubliee. And if you want to really understand the evolution into today, check out the episodes with Justin Carter and Eamon Harking (Part 1 / Part 2).